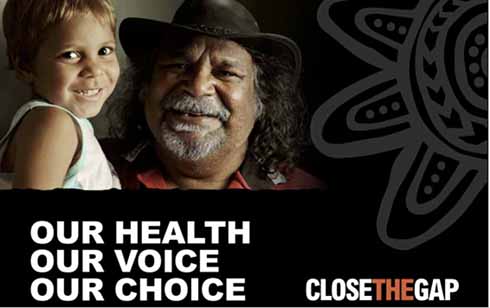

National Close the Gap Day is a sobering occasion each year. It records the gap between promises and actions, between aspiration and outcome. This year the theme of the Day is Our Health, Our Voice, Our Choice. It follows the National Closing the Gap agreement signed last year setting out the targets and hoped for outcomes for Indigenous well-being over the next ten years. That is the aspiration.

National Close the Gap Day is a sobering occasion each year. It records the gap between promises and actions, between aspiration and outcome. This year the theme of the Day is Our Health, Our Voice, Our Choice. It follows the National Closing the Gap agreement signed last year setting out the targets and hoped for outcomes for Indigenous well-being over the next ten years. That is the aspiration.

The associated Close the Gap Committee report on the 10 years following the first National Closing the Gap agreement was depressing reading. It pointed to the ways in which Indigenous Australians continued to trail other Australians in length of life, in vulnerability to illness, in quality of health care and in all the social factors that contribute to good health. These include food, education, employment and community participation in matters pertaining to their own welfare.

Central to the 2018 report was its insistence that good health is not simply a service but is the right of all human beings, which nations and governments have a duty to respect. The rights of Indigenous Australians to demand and enjoy good health is taken up in the theme of the day: Our Health, Our Voice, Our Choice. Indigenous Australians are not beggars who should be content to be fed by the crumbs that fall from the Government’s table.

Tellingly, this insistence on health as a right is echoed in the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety. In both cases the demand for a rights based approach suggests that aged and Indigenous Australians suffer because governments have regarded their commitment to them as optional. That is the current outcome. And we have seen its cost in the stories told at the Royal Commission and in the deaths of three Indigenous Australians in prison during the past week.

Human rights are based in the conviction that each human being is precious regardless of age, race or way of life, and must be respected. They may not be used as means to economic ends. Humanitarian organisations such as Jesuit Social Services recognise the implications of this claim. Relations with people who are vulnerable through age, race, history or health must begin by attending to them as persons and to the relationships that help shape them. The political and institutional must develop out of the personal. Respect defines relationships between persons and only then processes.

This starting point in persons is important because it means that care for Indigenous welfare must not begin with economics – allocating a sum of money to it – and then devising policies that will match it. It must begin with persons, their health, their needs, their histories and their communities, and then ask how their needs can best be met.

If Indigenous inequality is to be addressed, our health, our choice, our voice must be the voice, choice and health of Indigenous people and their communities, not the health, choices and words imposed upon them in the name of economic benefit to others.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES

Making good decisions and developing resilience – questions and activities

These classroom questions and activities explore making good decisions like the Good Samaritan and being resilient like Jesus. They also examine contemporary contexts, such as resilience through faith in sports and making good decisions on significant issues.