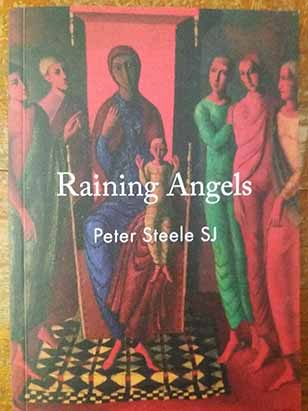

Peter Steele SJ, Raining Angels, Newman College, edited by Sean Burke, 2021, ISBN 9780645359008

Peter Steele SJ, Raining Angels, Newman College, edited by Sean Burke, 2021, ISBN 9780645359008

Sean Burke has put us in his debt by selecting and publishing the late Fr Peter Steele’s poems based on scriptural texts. Most were written in the last years of Peter’s life. They are spaciously laid out, with one poem to the page. On the facing page of each is the Gospel story on which they are based. The high quality of the poetry is matched by their attractive presentation.

Many critics dismiss the possibility of religious poetry. Although that claim sometimes reflects pure prejudice, it also draws attention to the challenges that face poets when writing on religious themes. They can easily be drawn to focus on how their readers might respond, or on whether their poem is faithful to the Gospel or orthodox. More fatally, they may slip into using in unconsidered ways religious language and imagery that may have lost their original sharpness. The result can then display a sentiment for which no price has been paid and an untested reassurance. The poem becomes a work not of discovery but of construction. It might be described better as religious verse, certainly worthwhile in itself, than as religious poetry. This challenge, of course, is not confined to poets writing on religious themes. Poets laureate, for example, face a similar challenge when writing poems on civic events.

Peter Steele’s poems on the Gospel stories avoid these temptations to introspection and to the comfortable. He does view the scenes from the perspective of one of the participants or of a hard-headed observer. He begins by imagining the concrete, physical details of the story. The restrictions imposed by Steele’s preference for short poems, formal in their structures of rhyme and rhythm, force a compression that at the end of the poems is released into the possibility of something beyond the scene. In ‘Watch’, for example, a poem based on Jesus’ appeal to the beauty of the flowers in the field, the poem fills out for the reader the attention that underlies Jesus’ generic reference:

Tulips were in the hills, and chamomile

To flag the acres; crown daisy, fast to fade,

And as for lotus, the eye could almost steal

A heaven from the steady blue displayed.

The couplet that concludes the poem turns the reader’s attention to the person who could see and wonder at such beauty and to the perils of this gift when the watcher becomes watched.

Time was, nobody cared what he could see;

They learned, though, how to watch him carefully.

Many of the poems in Raining Angels focus on the arrest, trial and execution of Jesus at the end of his life. The horror of the systematic obliteration of humanity in Roman executions is presented, all the more starkly because it is observed from the perspective of those to whom it is everyday business. The poem ‘Moron’ looks unflinchingly and sardonically at this brutality:

It’s moron time, so now he’s out on the flags

To get some thorny bunnet into his head

And more than a touch of scarlet, as the wags

Affect belief in what, a king, he said.

Backhanding’s how they do it here, the face

Worked to a ball of meat and bone, the eyes

A dullard’s willy-nilly as the lace,

A whipsaw reed’s achievement takes the prize.

After this scene in the guardroom, the final couplet invites the reader to see the events from the perspective of Pilate and his wife within the palace:

Inside the governor’s reasoning with his wife;

Dreams, as he knows, have nothing to do with life.

Pilate’s confident claim, invites us to ask whether this indeed is what we ourselves and God know.

The tightness of the sonnet form and the weight that can be placed on the final couplet also allows the poems simultaneously to reinforce the systematic and final dismantling of the victim’s claim to humanity involved in Roman execution, and to open the path to paradoxical possibility. In ‘Simon’, after describing the humiliation experienced by Simon of Cyrene’s humiliation at being forced to assist the dehumanised Jesus to bear his cross to the place of death, the poem finishes:

When it was over and the dead thing left,

He felt, as never before or since, bereft.

Simon and the reader have simultaneously to reckon with the obliteration of Jesus from a person into a thing and with the possibility of an unexpected response to him as a person.

In these and in the concluding lines of other poems the reader is invited to respond to the possibilities opened to them as well as to those once brought into contact with Jesus. One of the most haunting of these invitations is found in the couplet that concludes ‘Samaria’, the story of the Samaritan woman whom Jesus meets at the well.

The jar forgotten as he talked, she found

Herself at last, testing the native ground.

We are left wondering whether the woman and we the readers find ourselves in the encounter, or we merely find ourselves testing. We wonder, too, whether we, like the woman, are called to test the expressions of faith in which we were raised, our native ground, and whether Jesus asks more of us. Possibilities of conversion are held out but not defined.

Good poems always leave the reader free. Peter Steele’s poems are good poems, good religious poems.