People sometimes complain that we Catholics often speak about joy but that our celebrations are boring.

People sometimes complain that we Catholics often speak about joy but that our celebrations are boring.

The prayers during Mass tell us how happy we are to celebrate this or that feast but our hymns sound better suited for funerals. And when it comes to real celebrations such as music festivals or demonstrations, we talk more about their dangers than about how exhilarating they are. Catholic joy is altogether a weaker brew than ordinary joy. These charges are an exaggeration, of course, but if they are true, it’s a pity. In this Explorations we shall look at the place that joy and celebration have in our Christian faith and our lives.

HAPPINESS AND JOY

Many priests will tell you that joy is one of the hardest topics to preach on, because you need to look and sound joyful when you speak. They tell the story of a glum-faced priest whose sermons were always full of gloom and doom. When he came to the text, ‘Rejoice in the Lord always, again I say rejoice’, he frowned at his congregation and thundered, ‘Today’s reading says you’ve gotta rejoice. So get on with it, rejoice!’

In real life joy can’t be turned on and off like a water tap. It is also elusive. If a friend asks us whether we are happy we might struggle to answer. We may think that we are happy enough, but we wonder whether our friend would regard what we see as happiness as real happiness. They might even see it as sadness. We know what unhappiness looks like, but find it harder to put a finger on joy.

Joy goes deeper than feeling good, being on a high, or acting happy-clappy. When we say that someone is joyful, we point to a quality of spirit that lies deeper than their surface feelings. We may know people who have suffered great loss and have grieved deeply, but who still strike us as joyful. They will surely experience feelings of sadness, anger, compassion and fear, but they also radiate a deeper interior joy. Pope Francis is a striking example. He expresses anger, grief and fear for the future of the world, but impresses those who meet him most of all by his joyfulness.

JOY IN SCRIPTURE

In the Scriptures joy is associated especially with the future. The prophets, many of whom lived during a time of exile, threat and of infidelity to God, promised a future when God would rescue the people from the tears and toil of exile and bring about a joyful return to Israel. This would be a time of rejoicing, companionship and plenty. It would be a changed world in which people attended carefully to God’s word. In the New Testament, too, Jesus compared the coming of God’s kingdom to a feast to which everyone was invited. In the Gospel he is often criticised for eating and drinking with disreputable friends.

The deep joy in the lives of the early Christians flowed from their faith in the crucified and risen Jesus. Although their joy often was accompanied by grief and fear of persecution, it remained with them because they had great hope. When they came together to celebrate Jesus’ life and death for them, they tasted the joy that they would fully enjoy later.

In the Scriptures, joy is not something you can force yourself to feel or can practise. It is a gift that comes with the conviction that God has made you for happiness and is with you wherever your life takes you. They believed that in Jesus God has joined us in our lives, experiencing all the disappointments and hatred that threaten to strip us of joy and hope. They believed, too, that Jesus had risen to a new life which he would share with all those who followed him. Their joy was not something they had to rev up inside themselves but was a gift of the Holy Spirit whom God had sent to be with his people.

SHARING JOY

When Christians met they shared their joy in ordinary and messy ways. Some Christians were naturally cheerful and extroverted, good people to invite to any party. Others were introverted and reflective, good people to chat with when you had something on your mind. Others were enthusiasts who easily became discouraged or disillusioned at how ordinary their fellow Christians were. In the communities they formed, joy often went hidden behind the heavy clouds of weariness, loss and rivalry.

At the heart of their lives, however, were their regular meetings to celebrate the Eucharist and the Baptisms, anointings and other events in the life of their community. Thanksgiving for the life and death of Jesus whom they believed to be present with them brought them together to remember his life and death. It may sound odd to come together to celebrate a violent death such as Jesus’ crucifixion. But when remembering Jesus’ death the early Christians focused on the great love of God whose Son had died and risen for them. His death had brought them life. That is why their celebrations expressed joy and thanksgiving. The word Eucharist reminds us of this: it means gratitude.

THANKSGIVING AND CELEBRATION

Gratitude can become a basic attitude in life. In the daily lives of the early Christians the default position was not one of disappointment, complaint, surrender or getting on with it. It was one of gratitude for the gifts that God had given them in the beauty and fertility of the world around them, for the people around them, and for the possibilities in each day’s encounters, even the unpleasant ones. They saw their lives and above all their calling by Christ as a gift. Their gratitude was the foundation stone on which joy was built.

Gathering together in thanksgiving naturally multiplied occasions for people to celebrate. Gratitude for Jesus’ life and death sparked interest in the stories and the people of the Gospels. This interest in turn generated feasts and seasons when people could mark the events of Jesus’ path from God to us, and with us back to God. These events focused first on his death and rising, but later turned to his birth and public life. They extended then to the seasons of Mary’s life, and the events in local communities when the Apostles had first brought the faith, when local people had been martyred, and holy people had lived among them. All these events were remembered with gratitude and their anniversaries celebrated.

The celebrations became increasingly complex. The events around Jesus’ death and rising were preceded by prayer and fasting for a month, followed by the distinctive rituals, feasting and special foods for Easter. Christmas was surrounded by a similar rhythm of fasting and feasting, of preparation and of exuberance, that bred other forms of celebration – feasting, dancing, games, dramas and musical performances to remember the events of the season. The timing of these feasts often followed the rhythms of planting and harvesting. It associated prayer and gratitude for the gift of Christ with prayer to beg God for the safety of the crops and to thank God for the harvest.

The relics of this exuberance can still be seen in processions and dances and other seemingly quaint customs whose origin lay in a feast day. Gratitude generated joy, which overflowed from churches into the daily life of towns and villages. As in more modern times, too, the celebrations forgot their serious origins. Sermons from early times warned of the dangers of drunkenness and sexual license at the festivals, particularly among young people who were feared to have turned away from their religious upbringing.

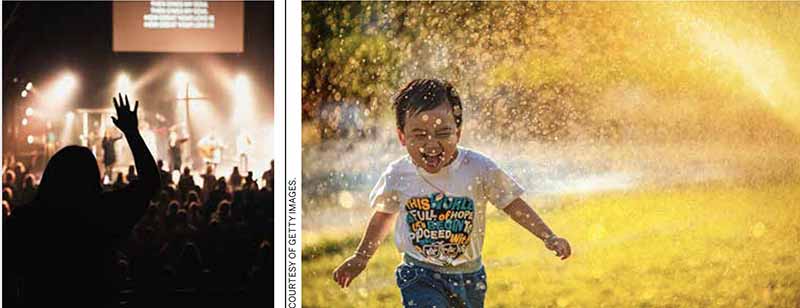

THE BUILDING BLOCKS OF CELEBRATION TODAY

Joy and thanksgiving have been central to Catholic faith and life from the beginning and have given birth to many forms of celebration. Our experience tells us how attractive joy is. We like to be with people who are joyful, and we see how they attract people to them. Joy builds community and shapes its life. Where communities are strong and happy, lively celebrations will follow. This is true of families who always find ways of marking birthdays, excursions and big feasts with celebration. It is also true of parishes where people enjoy being together, gather after Mass for a cuppa, have picnics for altar servers, working bees on the church and the school and, in rural areas especially, gather with the rest of the town community to cook, organise, and enjoy one another’s company at football matches, funerals and other occasions. Joy and thankfulness are built into the messy ways in which people come together as community and as church.

At a deeper personal level we are invited to welcome joy and thanksgiving into our lives so that they are not just virtues for fair weather but are strongly rooted enough to withstand the cold and the storms that the seasons of our lives will bring. For Christians our joy and gratitude flow from gratitude to God for the deeply felt gift of life and of the world into which he has invited us, and for the extraordinary gift of joining and giving life to us through Jesus.

The focal point for being grateful and being drawn into joy is Sunday Mass. As a community we remember and are joined to Christ as he gives himself to us in sharing the Eucharist. As the Sunday eucharist becomes part of our lives, it can sustain us in the hard times where life is tragic and seems thankless. We are drawn to gratitude and joy in our living, which in turn prepare us to celebrate the death of people whom we love and to reckon with our own mortality.

NURTURING THANKSGIVING

Joy and thanksgiving are not only Sunday business. They belong to every day in our lives. They are gifts that we are invited to nurture in our daily prayer and reflections. It can be particularly helpful to bring them into our lives during our day. Phrases such as this one from Psalm 33, ‘In the Lord I’ll be ever thankful, in the Lord I will rejoice’ can stay with us as we walk through parks, notice the beauty of trees, grass and flowers, and come from a deep conversation with our friend.

Noticing our blessings helps us to live fully and to appreciate the gift of being invited into such a beautiful world. The pressures and demands of the day then fall away, as we see ourselves as a deeply loved, tiny part in a beautiful world that has God has made. We see our living and dying joined to those of plants, insects, birds and animals in the world that God has made. That I should have been invited to be an infinitely loved part of such a world, and even more remarkably to have been invited by Jesus to follow him in this world by choosing life over death and love over gain, will seem an extraordinary gift. It contributes to a deep joy, and a thanksgiving that become part of our everyday lives.

Pope Francis once said that if we follow Jesus we don’t have to be sourpusses. Jesus encourages us to celebrate happily and thankfully.

Questions

- What have been some of the really good celebrations in your life?

- Have you met people who seem really joyful? How can you tell?

- What reasons have we Catholics to be joyful?

- Have you been to celebrations of Mass when you felt happy and thankful?

- What helps us to be thankful people?