Elsie Heiss found solace in her faith as she grew up, created a community where she could feel at home, then spent much of her life helping the broader Catholic community grow in their understanding and acceptance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Life’s foundational lessons – wisdom, faith, the cost of prejudice and the infinite value of education – materialised from a single incident on a school bus in Griffith, NSW when Elsie Heiss was around nine years old. A white child had spat on her and called her names so derogatory ‘I can’t even repeat them’. Later, she recounted the experience for her father.

‘I said to my father, “I washed spit off myself today, from a white kid on the bus”. And he said, “What did you do?” I said, “I wanted to punch them, but they’d have chucked me off the bus”. He said, “Yes, and they’d have chucked you out of school as well. You need an education. The only way we Aboriginals are going to survive in this country is through education, because that’s the only way we’re going to gain respect”. He said, “Be like Jesus and turn the other cheek”. I said, “Daddy, I’m not Jesus. Jesus turned the other cheek, I want to hit ‘em in the cheek”. He said, “And then they’ll chuck you out of school, you’ll have no education. You’ve got to educate those white fellas what racism’s about, and the only way you’re going to do it is through the church, because that’s the only place you’re going to be accepted”. My father was a wise man.’

Wise, and prophetic, too, for the now 83-year-old Aunty Elsie has spent her life advocating for the Aboriginal community from her position as a deeply cherished member of the Catholic Church.

It’s a faith she’s carried with her since her birth on Cowra Mission in 1937 to parents whose own faith was shaped, paradoxically, by the government’s punitive Aboriginal policy. Her father, Jim Williams, had grown up on Brungle Aboriginal Reserve near Gundagai, and had later acquired his faith from his manager on the sheep station where he was employed under the care of the government; her mother, Amy Jospehine Talence, was a member of the Stolen Generation and was placed in a training college in Cootamundra for Aboriginal Girls who had been taken away from their families.

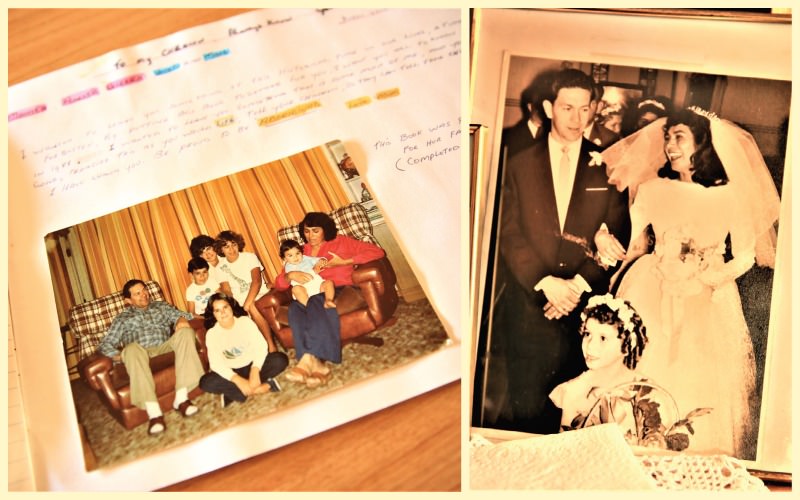

While in service for the government, Amy met Tilly Williams and became a pen friend of her brother, James (known as Jim). Jim and Amy communicated by mail until Amy was of age to leave government control at 21; they married on Brungle Mission Reserve when Amy was 22 and Jim 27.

STRONG IN FAITH, STRONG IN CULTURE

‘[My mother] was strong in faith and strong in culture, but I think she was stronger in faith than culture,’ Elsie says. ‘[My father] taught her most of her culture, because she’d lost it.’

Friday morning masses at home were a feature for Elsie and her six siblings – with all the windows closed, she says, since the manager of this particular mission wasn’t Catholic, and his Aboriginal charges were expected to espouse his faith rather than theirs’.

‘We had to hide being Catholics,’ she says. ‘[But] my mother was a great ambassador for the Catholic Church, and so was my father. So we kept our Catholic faith going strong. It’s what kept us strong and kept us together as a family.’

After the death of Elsie’s younger sister from rheumatic fever (an illness Elsie herself was hospitalised with as a child), Jim moved his family off the mission and into Griffith, where they would no longer be held within the government’s clutches and where his children could attend a white school. But still, the family was poor, living in a dirt-floored humpy on the edge of town with no electricity or running water. At 15, Elsie left school to help earn a living.

‘I worked with my mother at the base hospital in Griffith – I was a ward maid, carrying the meals out, sweeping the floors. When I left there I worked in a boys’ school out on the Murrumbidgee River. But at 16-and-a-half I knew I had to get out of the country, I had to come down to Sydney . . . to get a proper job and get paid a decent wage.’

Elsie boarded with an aunty in Redfern and got a job in a chocolate factory; on her daily commute to work on the tram she befriended a group of young Aboriginal people from Kempsey.

‘I said to them, “I’m going to Mass on Sunday – is anyone coming?” And they said, “Yes, let’s all go together”‘, she recalls. ‘We went to Mass together [at St Vincent de Paul’s Catholic Church in Redfern] and after Mass we went to the football, and after the football we ended up at the same milk bar together. On a Wednesday night and a Saturday night we went to the dances together in Redfern.’

LOVE STORY

Meanwhile, Joe Heiss, a carpenter from Austria, had migrated to Australia in 1957, and met Elsie at a birthday party the following year. It was a blossoming love story; though their connection was strong and consolidated by a shared faith, it took time for Elsie’s family to accept the union. But the Williams family gradually softened, and Joe and Elsie were married in 1960 in St Vincent’s, the church in which she’d found succour when she’d moved to Sydney a little over six years earlier. Four years later, on a trip to meet Joe’s family at their home in the village of St Michael, south of Salzburg, it was Elsie’s turn to win them over.

‘[That] didn’t go down very well either, because, well, [I was] an Aboriginal, [and] they didn’t even know what an Aboriginal was, you know? We had five weeks on the boat – can you imagine what colour I was? His mother got the shock of her life,’ she says.

Elsie baulked when the older woman insisted she go to church with her; the lukewarm reception in this cold, foreign country had unsettled her, and she felt God had let her down. But arriving at the church among parishioners come to meet the new Frau Heiss, Joe’s Australian bride, she found something even more discomfiting than the stares of strangers.

‘The marble floors were cold and hard and [had] no cushions to kneel on. And I’ve got the skinniest legs in the world! My knees were on this hard marble floor and I thought, “this is the first and last for me, I’m not coming back here unless I got a cushion”,’ Elsie laughs.

Six months later, Joe and Elsie – now pregnant with the couple’s first child – sailed back to Sydney and settled in Matraville; Elsie still lives here today in the home built by Joe (who died in 2005), surrounded by his lovingly crafted furniture and photos of their children – Monika, Gisella, Anita, Josef and Mark – and seven grandchildren.

FAITH LEARNED IN THE HOME

‘It’s always been our family home, this is where they learned about their faith. They still talk about it. They’ll say, “Do you remember the Sundays when mum would get us out of bed? And what about the midnight Masses?” Joe would say to me, “You open the front door, I’ll push ‘em out”,’ she laughs.

‘We had a great life together, we had great children, everything to be thankful for. And he was a good Catholic – though he said to the priest up at Malabar [the family’s parish] one time, “Father, I hope you’ve got a place for me in mass ‘cause I’ve paid enough money to this church”. He said, “Every time I turn around, there’s an envelope from the school”. He had a great sense of humour.’

The loving family snapshots are accompanied by photos of Elsie meeting Pope Benedict, and Pope John Paul II, for whom she was asked to perform a smoking ceremony when he visited Sydney in 1995. But he had a cough on the day, and so Elsie wasn’t able to conduct the full traditional ceremony – though she’s certain the eucalyptus leaves would have cured him.

‘I smoked the Pope, but from a distance. He put the gum leaves in the fire [himself] and then shook them in front of him, and that’s the closest he came to getting smoked. Because if I’d hit him with that smoking bucket he would have coughed his way to kingdom come!”

With the children now mostly grown up, Elsie enrolled in a Certificate of General Education course at TAFE in 1989; she was also recruited, on the strength of her activism and her experience as a person living with diabetes, to work in the diabetes program for Aboriginal Health – a role she would fulfil for 15 years.

Already deeply involved in her parish at Malabar and a member of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholic Council (NATSICC), she teamed up with Father Frank Fletcher MSC to found Aboriginal Catholic Church Ministries (ACM) in Erskineville; the organisation became a torchbearer for issues of Aboriginal spirituality, reconciliation and justice. And a decade later, with the support of Father Pat Hurley, Elsie was finally able to secure an empty church in La Perouse – Our Lady of Good Counsel – for use as the ministry’s central place of worship, fellowship and learning.

‘We had our first Mass on the 4 November 1998,’ she says. ‘Nine people turned up, all Aboriginals. I thought, “Hello?” Nine people at the Mass and they’re all Aboriginals? We’re going somewhere.’

INVITED TO ROME

The excitement from that first Mass had barely subsided when Elsie was invited to Rome as the only Aboriginal representative at the Synod of Oceania.

‘I thought it was a challenge – a challenge by the church, a challenge by God. I thought, “Elsie Heiss, you’re going to do it”.’

When she landed in Rome just weeks later, a group of Marist sisters and fathers was waiting to meet her. She stayed with them at Via Cassia, and they would drive her to the Vatican each day during her three-week stay. Then one day they told her she had to deliver a presentation which would be transmitted around the world.

‘I thought, “I haven’t even got a prayer with me”,’ she recalls.

Elsie wasn’t computer literate, but she found herself completing her presentation at 2am with the help of a journalist from Canberra, Barbara Brady.

‘She said to me, “You write it, I’ll type it”. And everything went good, I did the whole presentation and they said it went everywhere but Australia. But it’s gone to South Africa, gone to America, it’s gone everywhere.’

And Elsie didn’t waste the remainder of her time at the Vatican, lobbying every bishop and priest she could corner during tea time. This was where her career as an activist took root.

‘It got serious for me then. It wasn’t just doing mass at La Perouse once a month.’

On Elsie’s return to Australia, the church’s name was changed, appropriately, to Reconciliation Church.

‘Cardinal Edward Clancy… said, “You have now reconciled the community with the Synod of Oceania, which wasn’t recognised before”. We celebrate reconciliation out there every year. It’s a big thing now in the Aboriginal community, and the church being named after that means something to Aboriginal people.’

In the years since, Elsie, has become an elder of her community, a tireless activist, educator, inter-cultural and inter-faith bridge-builder, and keeper of Aboriginal culture and identity and the stories of her mother’s Stolen Generation. Her work with the Reconciliation Church led her to Darwin, where she completed a Theology Course at the Aboriginal Catholic College. At NATSICC, she’s served as both chair and treasurer – a position she still holds today. And she’s received numerous honours and awards, including an honorary doctorate from the University of Notre Dame Australia.

ECUMENICAL AFFAIR

The Aboriginal Catholic community in La Perouse has diminished over the years, much like Catholic communities in general; but is, for the most part, as culturally steadfast as it was when Elsie founded it all those years ago. Masses are an ecumenical affair, encompassing sacred Aboriginal traditions such as the welcome to country and an Aboriginal Our Father said to the rhythm of clap sticks. Some of the Aboriginal elements have disappeared over time, Elsie laments, such as the Aboriginal references in the creed and the dousing of smoke during baptism.

‘We need strong Aboriginal visions and people, but they’re not there anymore. They’re all passed on.’

But the Reconciliation Church still fills Elsie’s spirit. Recently, she returned after an eight-week, social distancing-inspired hiatus, and said the prayers of the faithful during a livestreamed mass.

‘It was the most wonderful day of my life in a long time to go into church and meet so many people [I know],” she says.

‘The priest said, “Aunty Elsie, having you here is an inspiration to us all because we missed you so much. You were the one that created this church. I said, “But I’ve had lots of help along the way, all these people that are here today are the people that started with me”. I said, “These are the blessings that we have. Count our blessings, because we are blessed”.’